The Jewish Story of Venice, Italy

It’s a scene most of us picture when we think of Venice: rows of shiny black gondolas, gently bobbing on the water. Gondoliers in striped jerseys loll against weathered dock posts, drawing lazily on cigarettes as they wait for their next fare. Behind them, across the busy waterway, rises the unmistakable dome of Basilica di Santa Maria della Salute. Turn around and you’ll be facing the magnificent Doge’s Palace on the fringes of iconic St Mark’s Square. There are few places as beautiful in all of Italy.

Stroll a while, ducking down narrow alleyways and crossing tiny bridges, loosely following the sweeping curves of the Grand Canal. Before long you will reach the northernmost of the six historic sestieri of Venice. This is Cannaregio, the focal point of the city’s Jewish community. Packed full of historic landmarks yet off the beaten track, it’s one of the most rewarding parts of the city to explore.

Jewish life in Venice: turbulent beginnings

Blessed with such a distinctive culture, it feels like Italy has been around forever. But in fact, it didn’t exist as a nation before 1871. Instead, the country as we know it was a collection of city states and independent republics. One of the most influential was Venice, “La Serenissima”. A maritime republic that had earned a substantial fortune through trade, it thrived for over 1100 years.

Business needs funds and in Venice, Jews were welcomed as money lenders. However, anyone looking for permanent resident status in those early years could forget it. In 1385, though, all that changed. Conflict between the Venetians and their neighbors in Chioggia brought about a need for even more money. It forced a change in Venetian policy. Nevertheless, although Jews could now settle in the city, the largely Christian population neither trusted nor assimilated them. For more than a century, things jogged along, but it was an uneasy relationship.

The birth of the ghetto

Things came to a head in 1516, when a decree from Doge Leonardo Loredan established the Venice ghetto in Cannaregio. The name was no accident. The authorities cleared metal workshops to make way for housing; in Venetian dialect geto means foundry. Over time, geto became ghetto and now indicates a place where a minority group settles.

Under Venetian law at that time, Jews could run a pawn shop, lend money, trade textiles and practise medicine. But to do so, they had to live within the ghetto. Hastily erected walls blocked off parts of the Ghetto Nuovo that opened onto the canal. Locked gates confined Jews overnight and they even had to foot the bill for the security guards they never asked for.

At its peak, the ghetto was home to around 5000 Jews. They came from Italy, Germany, France, Spain and the Ottoman Empire. Each group built its own synagogue and maintained a separate existence. Everything changed in 1797 with the arrival of Napoleon. When he marched into Venice, he tore down the gates and abolished the ghetto restrictions. Those who could afford it departed for more affluent and desirable parts of the city, but returned each Sabbath to worship at the ghetto synagogues.

Post holocaust

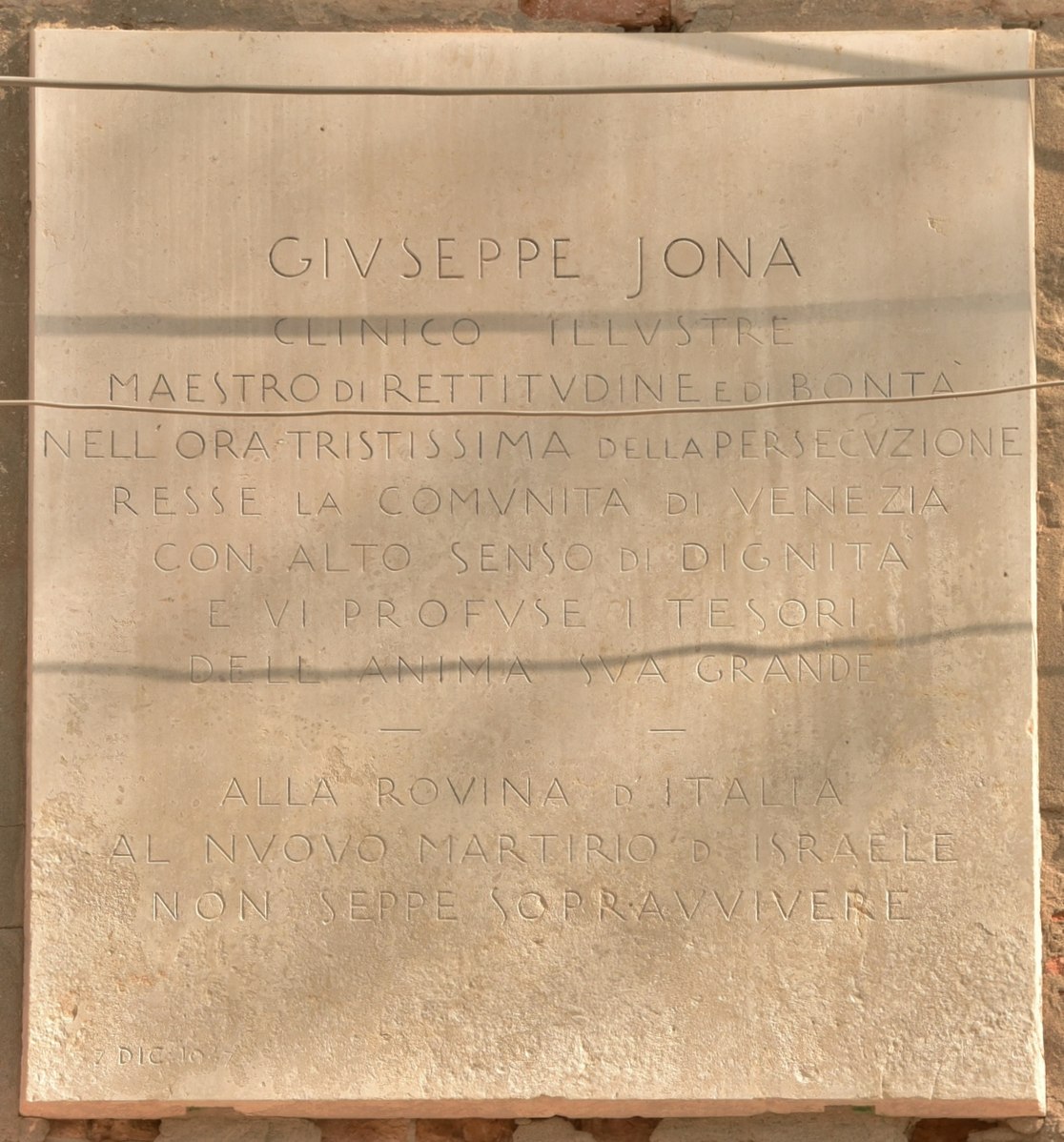

By the outbreak of World War II, about 1200 Jews lived in the Venice ghetto. The Nazis rounded up and deported more than 246 of them to Auschwitz. Fewer than ten survived. Yet, the figure could have been much higher if it hadn’t been for the sacrifice of Giuseppe Jona, then leader of the Jewish community.

The time, the Nazis demanded that he hand over a list of all the Jews in the ghetto. In an act of selfless bravery, he destroyed every written record he had that identified Venetian Jews, and committed suicide. A plaque in Campo di Ghetto Nuovo commemorates his sacrifice. Post-war, Venice has experienced a rapidly declining population. Today, around 450 Jews reside in the city. Thanks to high rents, only a privileged few can afford to live in the ghetto itself.

Exploring the Jewish quarter of Cannaregio

Broadly speaking, Jewish Cannaregio comprises the Ghetto Nuovo, the Ghetto Vecchio and the Ghetto Novissimo. A quirk of history, the Ghetto Nuovo was actually settled by Jews before the Ghetto Vecchio. The Ghetto Vecchio and Ghetto Novissimo were incorporated as the Jewish population grew.

A good place to start exploring is in Campo di Ghetto Nuovo. A bronze memorial to the horrors of the Holocaust is set into the brick wall of the square. Sculptor Arbit Blatas created “The Last Train” to depict how Jews were mistreated. The names of the victims are carved into wooden planks. As you stroll through Cannaregio, look out for stumbling blocks. These tiny brass plaques form a memorial by German artist Gunter Demnig. Find them along Campo Ghetto Vecchio and Campiella Santa Maria Nova.

The Jewish Museum hosts guided tours of the area’s synagogues. The central European Ashkenazim built the oldest, the Scuola Grande Tedesca, in 1528-29. They were also responsible for the Scuola Canton which dates from 1532. The third synagogue in the Ghetto Nuovo is the Scuola Italiana, erected in 1575, which served the Italian Jews.

In the Ghetto Vecchio, you’ll find two Sephardic synagogues. Prosperous Levantine Jews built their synagogue in 1541. Its interior boasts an intricately carved wooden ceiling and bimah (pulpit). Close by in the Calle del Forno, a bread oven was used for making Matzah. Nearby is Scuola Grande Spagnola, the Spanish synagogue.

Renaissance man: Rabbi Yitzchak Abarbanel

Rabbi Yitzchak Abarbanel was born into a well-connected family that advised royals and rulers in Portugal and Spain. Philanthropist at heart, he worked tirelessly on behalf of the Jewish community. However, in 1492, a decree forced Jews to convert to Christianity or leave Spain. He chose the latter option and sailed for Italy.

Eventually he wound up in Venice and joined the government. As a respected statesman of the Venetian Republic, he led negotiations for a spice trade agreement between Italy and Portugal. Later, he dedicated his life to study. By the time he died in 1509, he had secured a place for himself in Venetian history.

Next time you find yourself in Venice, why not take a walk in his footsteps and explore Cannaregio for yourself?